Back in the day when I rode my bike 100 miles to school – in the snow – barefoot – I learned that there were competing ideas about who was the first real fictional detective. Edgar Allen Poe gets first dibs as his short story, “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” arrived in 1841. There are those who argue that it should be Wilkie Collins with his mashup of Poe’s original detective trope with Dickens’ world in The Moonstone. Little did we know there is one dark horse entry, “The Mystery at Notting Hill,” that some claim as the first. The author used a pseudonym, Charles Felix, and it took years to reveal his name as Charles Warren Adams whose serialized the story in 1862 for Britain’s “Once A Week” magazine.

These mysteries and their investigators were all male. I began to wonder who were the first fictional women detectives. I drew forth my literary research shovel and began to dig. Here’s what I found.

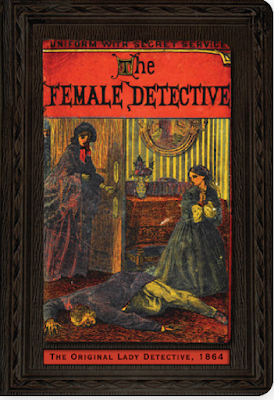

In 1864, James Redding Ware, authoring under the penname, Andrew Forrester, delivered The Female Detective.

It was a collection of detective stories narrated by “Mrs. Gladden.” Mrs. Gladden, while seen merely as a dressmaker, investigated for clues, used deductive reasoning and her own knowledge of medicine. She called herself a professional detective. What’s more, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s epitome of observation and deduction, Sherlock Holmes, used these same techniques much later in 1887 when he published his first Sherlock story, “A Study in Scarlet.”

Mrs. Gladden, like most PIs, thought the police a bit dim at connecting dots.This is a trope that has endured to this day; the private detective is always smarter than the cops. In her mysterious murder-solving, she is as dogged and detailed as C. Auguste Dupin in Poe’s “Rue Morge”.She rifles the dead man’s pockets.She observes the hair and skin of the victim to deduce he was murdered by a foreigner.

Mrs. Gladden set the model for all fictional private detectives that came after: observation and hypothesis, followed by deduction and solution.

The lady as sleuth took off in the Victorian England. In 1880 William Stephens Hayward created Mrs. Paschal for his 10-part series, Revelations of a Lady Detective. Mrs. Paschal was far more daring than her predecessor. She smoked. She carried a handgun. She would even rip off her crinoline to descend into a sewer to search for clues. A widow, left in dire financial straits by the death of her husband, Mrs. Paschal was certainly not considered as performing “a woman’s work.” In these stories, she works with the official police force, though she also occasionally makes herself available as a private detective.

The rest, as the cliché rolls, is literary history. A man may have created our first female sleuth, but quickly others followed. The Victorian era bookstores soon exploded with new women investigators.

There was Mollie Delamere, another fictional detective, appeared in 1899. She was a young widow employed as an international pearl broker who had to outsmart the countless burglars after her wares. In 1900, Hilda Wade arrived. She was a brilliant nurse solving medical mysteries to get close to the physician who framed her late father for murder and who ends up on a globetrotting adventure to catch him. Dora Myrl, who first appeared the same year, was a youthful woman in ankle-showing skirts with an advanced degree in mathematics from Cambridge – a medical doctor who couldn’t find work as a physician, she begins working as a private eye. There were also many more ladies saving the day: Loveday Brooke (1893), Lois Cayley (1899), Hagar Stanley (1899), Florence Cusack (1899–1900), Judith Lee (1911–16). American counterparts included Laura Keen (1892), Amelia Butterworth (1897), Frances Baird (1906), Madelyn Mack (1914), Violet Strange (1915), and Millicent Newberry (1917).

The detectives above are but a small selection of women who got it done as they charged the boundaries of male sleuthing. They slipped the bonds of female stereotyping and we’re going to keep on reading their adventures. For fans of historical fiction and champions of women’s competence, I encourage you to explore these lady investigators. You will be richly rewarded. There’s good reason their stories are still in print.